Being an entrepreneur isn’t for everybody. I tend to think it’s something you’ve either got in your blood or not. Regardless of the hardships, the excitement, the ups and downs, I think those who have the bug will become entrepreneurs no matter what. So for those who take the plunge, here are some things I experienced when I started GreenLine Legal.

1. You’ll have trouble getting people to pay attention. If you came from a well-recognized company or firm, that name has real power. Especially if you were a junior person at your previous employer, people would listen to you because of the brand name (and all that time you thought it was because of the valuable things you say…). As an entrepreneur, you need to prove yourself, over and over again.

2. It can be very lonely. Starting a company requires you reach far down into your reserve of self-confidence. Remember the scene in “There Will Be Blood” when Daniel Plainview is chipping away by himself in his oil prospecting mine (and then breaks his leg and almost blows himself up)? You must be comfortable going it alone, though of course having a co-founder or two significantly eases the psychological (and literal) burden.

3. Nothing happens unless you make it happen. If you don’t build your product, nobody else will. If you don’t sell, market, negotiate, plan, hire, manage or raise capital yourself, it won’t get done. You lose the comfort of having others to cover for you in a pinch.

4. Nobody tells you what to do. This is perhaps the biggest mental change when you start off on your own. You can (and should) get advice from those who have been through it before, but nobody will tell you where you need to focus each day. This is actually one of the best parts of being an entrepreneur once you get used to it.

5. You are responsible for what happens. Responsibility, for those who take it seriously, is hard. Sure, there are benefits of being in charge, but if things go wrong, you take the blame.

6. People won’t understand what you’re doing. This is particularly true for people who aren’t your target customers. The usual response that I’ve heard again and again is, “Well, that’s very exciting!”, similar to when you told your parents you wanted to become a rock star. I think this is really just a cover-up when people think you’re off your rocker and are building some bizarre contraption that nobody will want (though of course this isn’t the case with you…).

7. You’ll be afraid. At least in my book, fear is the inevitable companion to entrepreneurship – fear of screwing up your career, burning through all your money, watching your classmates and former colleagues rise in their professions, rejection by customers and on and on. Fear is an emotional reaction to risk (risk = uncertainty x severity of consequences), and as such, some people feel more, others less. But however much anxiety you experience, you need to find a way to live with it. Reduce risk by (i) decreasing uncertainty and (ii) decreasing the severity of consequences. Decrease uncertainty by doing things that make it more likely you’ll succeed – listen and understand your customers, carefully budget your resources, get advice from those more experienced than yourself. Decrease the severity of consequences by taking small steps and scaling – make incremental changes where failure won’t make or break you and don’t incur big expenses before you actually need to.

8. You’ll make many mistakes. You’ll be making decisions in the face of massive uncertainty. Some of those decisions will be wrong – it’s best to accept this and try to learn from them. Avoid getting into a decision that is make-or-break by taking incremental steps.

9. You’ll hear “no” more than you ever have before. If you’ve done well in school/work/sports or whatever, you won’t be used to hearing no. You might have gotten a couple no’s from potential employers or the schools you applied to, but the ratio of no’s to yes’s wasn’t anywhere near where it is when you actually try to sell something new. It’s hard when people say no. You want to blame them or think they don’t understand the value of what you’re offering. But you’ve got to learn from them – they will tell you critically important information if you dig a bit deeper.

10. Am I employed? Starting a company is nothing like “having a job”. It doesn’t feel like work. On one hand, it’s lots of fun, but on the other, it’s seven days a week, think-about-while-you-can’t-sleep-at-night, live, breathe, eat, drink work. It’s gritty. You’re in the trenches. If you gave up a decent salary or a well-known employer to start your company, you’ll need to get used to doing without this buttress to your self-esteem.

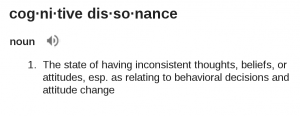

11. High Highs, Low Lows. It’s a bipolar existence – one day you think your company is going public, the next you’re about ready to start looking for a “real” job. I wish there was a better way to dampen the swings, but I think until you’re either profitable or at least scaling a verified business model, it’s up and down, over and over again.

Again, certainly not for everyone, but if it’s in your blood then nothing else can really compare. Each day you create something new – it’s the ultimate blank sheet. The rewards are consummate with the risk, though I believe many entrepreneurs’ minds are wired differently for computing risk. But whatever you do, successes and failures, ups and downs, just make sure you enjoy the ride.

I think part of the problem is the Technologist’s Handicap: as the creator of the product, you see all its limitations, all the bugs, all the places where you know it will get better with time. Also, you have a rationalist, logical mindset, you want to give people all the data and let them come, through a process of careful analysis, to the inevitable conclusion that your widget is worth its price. And technologists notoriously under-price. You don’t present hype, you present an argument. Sure, you can talk passionately about all the technological mountains you’ve summited, but your customers won’t care.

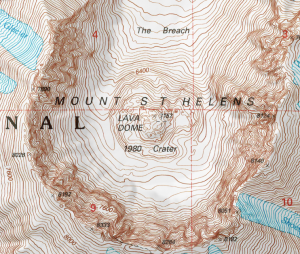

I think part of the problem is the Technologist’s Handicap: as the creator of the product, you see all its limitations, all the bugs, all the places where you know it will get better with time. Also, you have a rationalist, logical mindset, you want to give people all the data and let them come, through a process of careful analysis, to the inevitable conclusion that your widget is worth its price. And technologists notoriously under-price. You don’t present hype, you present an argument. Sure, you can talk passionately about all the technological mountains you’ve summited, but your customers won’t care.