I’m tired of people saying don’t be afraid of failure. Fear is an emotional response – you may as well tell someone not to be sad if his pet dies or not to be angry if someone bumps his car. Fear is part of being human. Sure, some people experience these things more acutely than others, but everyone – even a tough, serial entrepreneur – feels something.

Of course entrepreneurs fear failure. There’s just no way to avoid that – the challenge rather is to manage that fear so that it doesn’t have the perverse effect of making the big failures more likely.

When I started GreenLine, I had an acute fear of failure. I left a secure, well-paying job that most of my peers were steadily advancing in. So my reaction was to shrink from this fear by postponing the day of reconing far off into the future – either I’d run out of discretionary savings and would have to go back to working for someone else, or I’d be generating good cash flows. Success or failure would happen at that point rather than at numerous small points along the way. It was the exact opposite attitude that I should have been taking.

In hindsight, I should have embraced the doctrine of Fail Early, Fail Often. This is not the Silicone Valley saying “Fail Fast”, meaning your entire venture should either crash or be airborne in a short period of time (which Mark Suster persuasively dismisses), but rather the idea that I’d set a series of concrete goals that were testable within a reasonable period of time.

This may sound obvious to more seasoned entrepreneurs and executives, but for me it was a real revelation. As Eric Ries argues, if you just build something and put it out there to see what happens, you’ll always succeed – in seeing what happens! But entrepreneurs, who deal with staggering numbers of unknowns, must embrace the scientific method in their strategy – set a clear, disprovable hypothesis and test it in a way that ensures success or failure. Without this, there can be no real learning and without learning there can be no real progress. Sure, you might get lucky or might internalize this process in an informal way, but neither of those things are viable recipes for actually running a business.

For the product-focused tech geek (like myself), this is easy in terms of metrics (cohort analyses, revenue targets, etc.), but is much harder when you get to the human side of things – to actually talking to customers. The reason is two-fold:

First, there’s confirmation bias – you’re likely to attach more weight to data that confirms what you already believe. If you’ve built a product, you think it creates value, so every scrap of data from customer conversations that confirms this will stick out in your mind. I think a lot of entrepreneurs crash and burn on this point – you conclude way too early that you know which product to build and which customer to sell to. Fight this bias! Savor criticism. Love it – embrace it. Put it up on your wall and ruminate over it, not to the point of beating yourself up or getting discouraged, but just enough to counteract the tendency to hear only what you want to believe. Your customers just told you something very valuable.

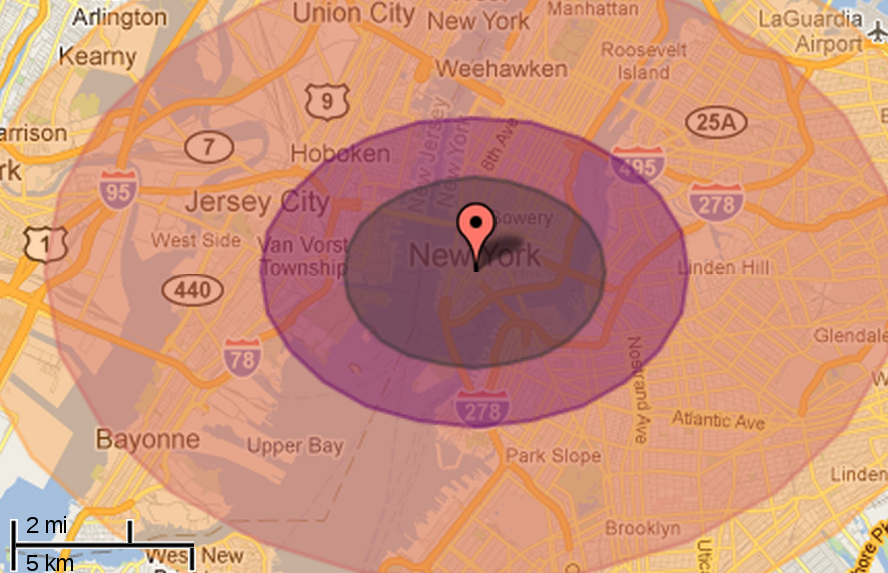

Second, most people don’t press hard enough to get past the polite BS that you usually receive. Good entrepreneurs, like good journalists, will press much farther than you’d go in a friendly dinner conversation. It’s easy to hear “This is really cool – everyone will be using it in a few years” and stop at that point. Great for team morale, but it doesn’t mean squat. Early on, we got a lot of these messages, but drilling down, it always turned out we had the perfect product for somebody else – never for the person we were actually trying to sell to. You need to (politely) press much, much further. Would you buy it now? Do you have the budget for the sticker price? How much would you pay? How often would you use it? How much value does it provide? Would you recommend it to a colleague or friend? How much time/money does it save? I have a hell of a time actually doing this – both because hearing criticism is unpleasant (let’s be candid here) and because I don’t want to make a potential customer uncomfortable. People also tend to be polite rather than honest (this tendency is in direct proportion with your geographical distance from New York City). If you don’t press, you’re avoiding your fears of failure instead of confronting them.

Second, most people don’t press hard enough to get past the polite BS that you usually receive. Good entrepreneurs, like good journalists, will press much farther than you’d go in a friendly dinner conversation. It’s easy to hear “This is really cool – everyone will be using it in a few years” and stop at that point. Great for team morale, but it doesn’t mean squat. Early on, we got a lot of these messages, but drilling down, it always turned out we had the perfect product for somebody else – never for the person we were actually trying to sell to. You need to (politely) press much, much further. Would you buy it now? Do you have the budget for the sticker price? How much would you pay? How often would you use it? How much value does it provide? Would you recommend it to a colleague or friend? How much time/money does it save? I have a hell of a time actually doing this – both because hearing criticism is unpleasant (let’s be candid here) and because I don’t want to make a potential customer uncomfortable. People also tend to be polite rather than honest (this tendency is in direct proportion with your geographical distance from New York City). If you don’t press, you’re avoiding your fears of failure instead of confronting them.

So the moral of the story is to manage your fears through pure habituation. Fail early, fail often. Set long term big goals and then work backwards to the present until you have a set of small, easy-to-test hypotheses. Each hypothesis should have a binary outcome – success or failure – in a reasonable amount of time. If you’re not failing pretty frequently, you’re either an entrepreneurial demigod or (more likely) you’re not being ambitious or honest enough with yourself. Savor the failures. Share them with your friends and family to help desensitize you. But most importantly, learn from each one. Learn why your experiment failed and take corrective action. Adjust future hypotheses if necessary. But don’t just run from these little failures – doing so makes the big failures an order of magnitude more likely.

Photo credit: Hirz/Getty Images

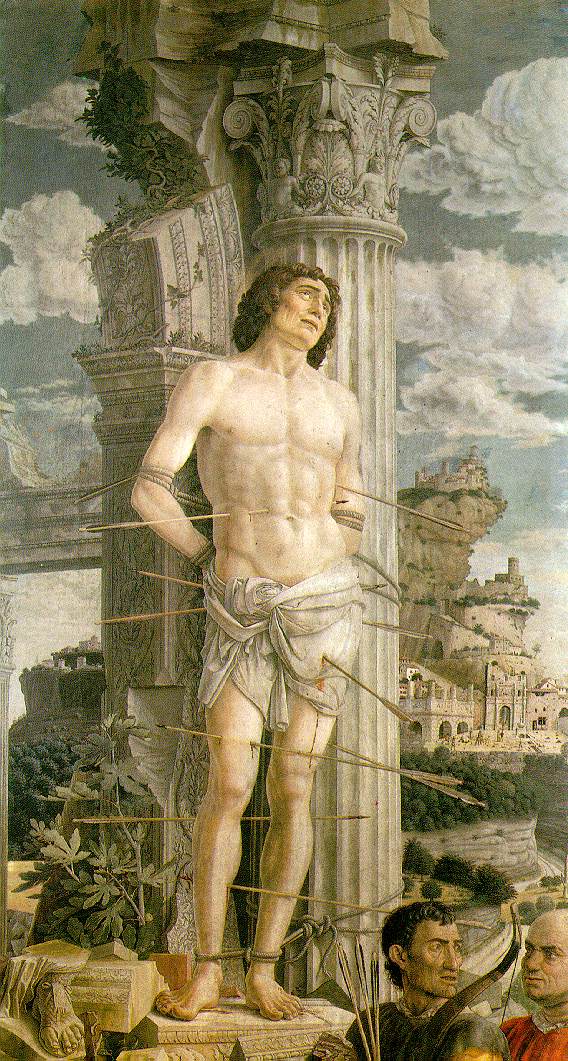

* Interesting story about St. Sebastian (the woeful looking fellow depicted in Andrea Mantegna’s painting above) – once a Praetorian Guard of Diocletian, he encouraged two imprisoned brothers in their faith and, despite being shot many times by archers as punishment, he pulled through (“‘Tis only a flesh wound!”) and was nursed back to health. Ever persistent, he then harangued Diocletian, was clubbed to death and thrown down a toilet. I visited Diocletian’s palace in 1999, located in present-day Split, Croatia.

Comments are closed.